‘The Circus’, bounded by its definite article, is an object; it’s countable (you could have three circuses, all separate, all nominally the same); it has defining features (even if we cannot put our fingers on them all); its edges are sealed, which can result in confusion and identity-crises.

‘Circus’, on the other hand, is a field, unbounded and unquantifiable; you can have versions of circus, but they contribute to the whole instead of being iterations of an archetypal original. A field holds room for difference within it. It is dynamic, unfixed.

My research is in the broad field of linguistics, and the specific version I focus on is Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). CDA scholars scrutinize the internal structure of texts and their social contexts to understand how different concepts or people are represented, what this means to the way they are perceived in the world, and how positive changes can be initiated. The way circus is represented to the public affects how it’s seen, which, in turn, affects how members of the public choose to engage (or otherwise) with circus products.

While a lot of that is out of our control – we couldn’t reshoot The Greatest Showman, erase 80 years of Dumbo, or edit out all the references to ‘circus’ in political reports, for example – there are changes that circus professionals can make to influence the cycle of representation and understanding.

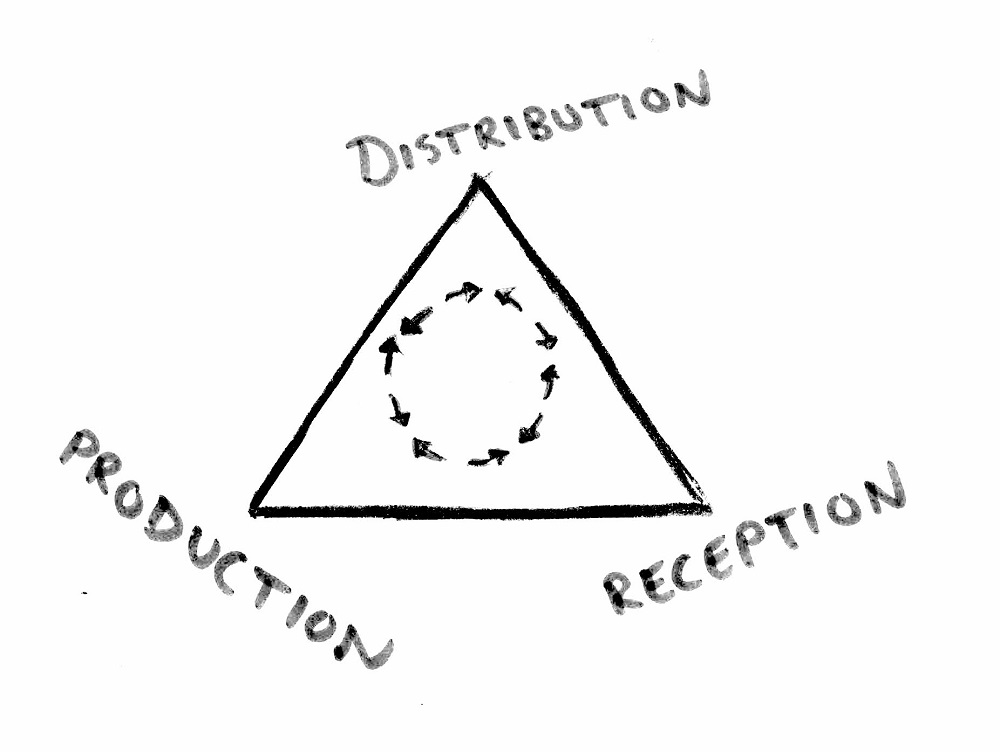

The relationship between creators and their audiences can be imagined as a triangle, where communication is mediated through promotional materials as well as through experience of live encounters (Figure 1). The way we talk about our work matters. The words we pick, the values we choose to communicate, the press releases we send, the classes we give, the dossiers we compose.

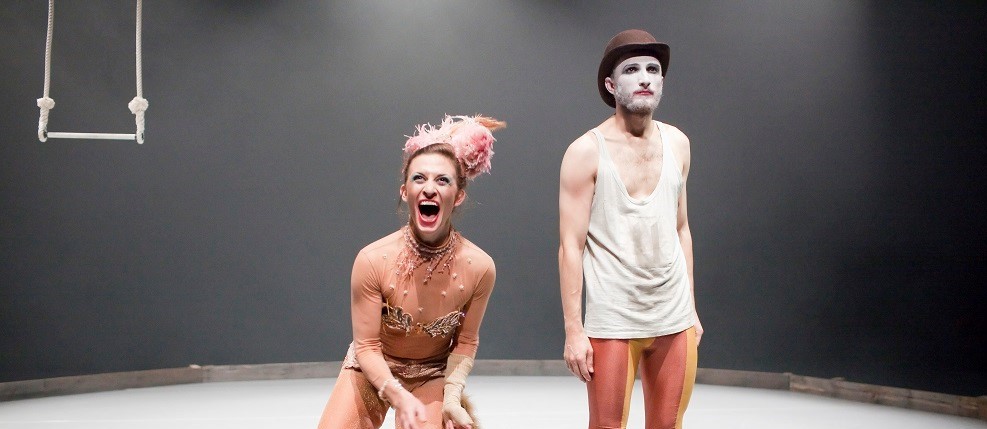

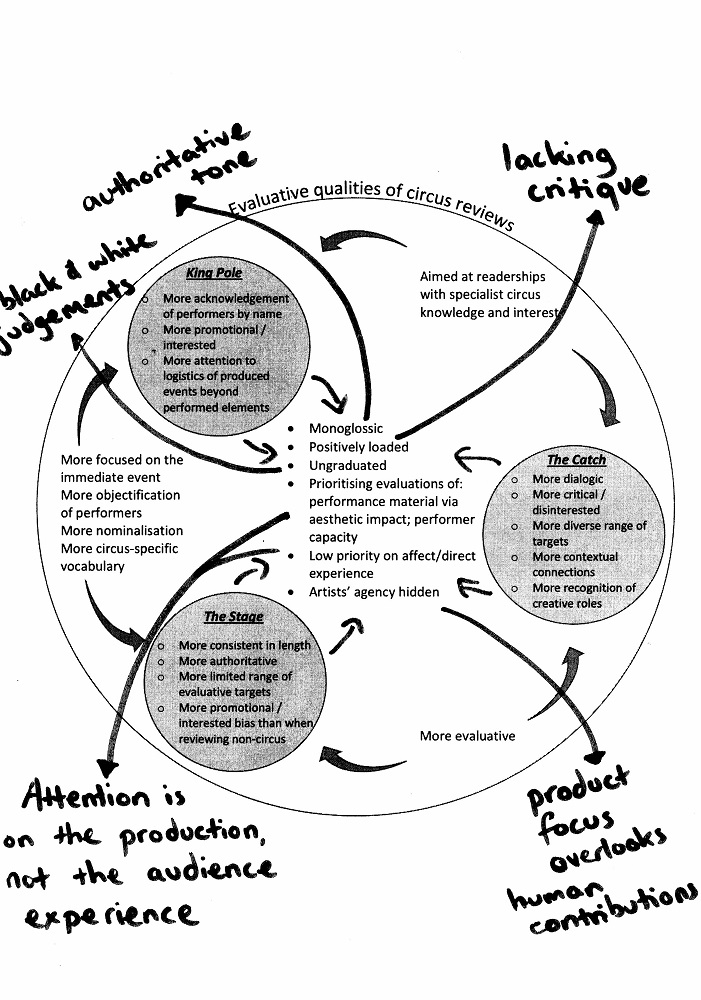

During my Masters in Language and Communication Research at Cardiff University last year, I conducted a study of circus review articles from three UK publications: The Stage (a weekly newspaper for the performing arts industry); King Pole (a quarterly fan magazine produced by the Circus Friends Association); and The Catch (a quarterly-ish magazine for the circus sector, originating within the juggling community). The Catch ceased publication in 1998, with only two issues a year for the final two years, so the articles compared were taken from all the 1996 editions of each publication. Since 1998, there has been no regular print publication for the circus sector in the UK!

My study investigated what elements of the circus experience were attributed value by the three different publications, triangulating two linguistic frameworks. What I discovered was not so much that the different groups of circus practitioners, circus fans and the general performing arts industry valued different elements of the experience, but rather that a much wider, more diverse range of values were expressed by the circus community, writing in The Catch, that were not reflected within the other publications (Figure 2).

If the full range of ways that circus can be considered important is not being communicated through the remaining publications that regularly review and discuss it, then this limits the ways that people may be encouraged to participate or attend performances. Right now, I’m at the very early stages of collecting and analysing data for my PhD. A recent online survey I sent out suggests that, competing favourably with the Nostalgia factor, Novelty is a highly valued element of attending circus performance in the UK. Perhaps more surprising is how often a sense of Community – relationships, intimacy and human connection – is mentioned. It’s a quality that circus practitioners have long-treasured, but how often is it used as a selling point to potential audience members? Whilst my analysis is still underway, I also want to highlight how Freedom seems to be emerging as a key value. Physical Virtuosity, Spectacle, Fun, and Excitement are also putting in strong appearances, along with Professionalism and Variety/Diversity. This is work-in-progress, and these findings might shift as I collect more data, but here they offer food for thought.

Because the positive slant to the cycle of understanding illustrated in Figure 1 is that it can be influenced from any point in the system. That includes by circus professionals. Unfortunately, it often feels safer to maintain the status quo. To use the words the funding bodies and bookers want to hear; that they’re used to hearing from theatre makers or dance artists (about ‘meanings’ at the expense of ‘sensations’ for example). Or to harness the conventions of ‘The Circus’ as a stable, mythical circus object rather than highlight what is fresh and dynamic about your own version of Circus. But the danger then is that nothing changes in wider understandings of what circus is and can be.

Shouldn’t 21st Century circus work be allowed to thrive on its own terms, rather than fit the models built for other forms? The answer, it would seem, is to be brave, be bold, be determined and be strong – all those things that circus is so good at – in putting out copy that speaks the language we want to hear from others. To talk about the core values that drive audience interest. To slowly start the wheel of understanding turning in a new direction.

References

Martin, J.R. & White, P.R.R. 2005. The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Scott, M. & Tribble, C. 2006. Textual patterns: Key words and corpus analysis in language education, Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

Sinha, C. 2017. Ten lectures on language, culture and mind: Cultural, developmental and evolutionary perspectives in cognitive linguistics, Leiden, Brill.

[1] These were: a) the APPRAISAL framework (Martin and White, 2005), which is a method of analysing evaluation in texts using the structure of Systemic Functional Linguistics; and b) the Corpus Linguistics technique of identifying Keywords, which are words that occur with higher relative frequency in one body of texts than another (Scott and Tribble, 2006:163).

[2] 231 responses. 49.4% had no experience in practising circus, 32% had experience training or in amateur performance, 18.6% had professional performance experience.