Tell us a bit about your work? What’s not in your show copy?

With Juliet and Romeo, I wanted to talk about relationships, but I wanted to talk about relationships in a way that felt kind of honest… and I also wanted to offer something that was kind of muddy, but somehow optimistic. And actually, the show isn’t that. The show takes a much more clear arc, and as a result, it simplifies lots of things that we wanted to say in the beginning. So I feel like if I’m really talking about the work honestly, then I would talk about the failure of it. I would talk about it like, ‘It was meant to say this, but it didn’t quite manage…this is where we got to when the premiere date arrived’. I suppose I know why that’s not in the description, because it’s basically a kind of spiral of doubt. It reflects the process and my uncertainty about the work. It opens up too many cracks and questions and basically, you’re just watching someone unravel!

Can you give us an insight into your curating and devising process?

There’s a lot of nothing happening, and kind of staring into space and waiting for I don’t know what. There’s mucking around playing games, sometimes just in order to do something. Moving, I guess, at the beginning of the day, making the body available to us for the rest of the day, even if we end up sitting on our asses. The idea that the body is kind of central is something I haven’t quite cracked, but the idea of moving at the beginning of the day seems to be a way of doing that. Like we don’t know why we’re moving, we can just improvise. We don’t have to generate material, we just need to kind of situate the body in the room and right here, so that later in the day, the body is still in a routine of finding.

I suppose directing feels like I need to be a bit more together, or I need to have a few more things up my sleeve, but ideally I want to work with people, or in an environment, where I don’t have to pretend that I know what I’m doing. I don’t like that feeling of standing in front of people and them assuming that I have answers. I like it to feel improvisational, like setting out exercises, and then watching them and trying to understand what I see in them. So if I’m directing, that’s really to do with the people that I’m watching. I feel like if you watch people improvise, you can kind of find the thing, that is their thing, even if not immediately. The directing process doesn’t feel efficient at all. It feels like I just have to trust that all of the shit that happens and all of the stuff that feels like it’s noodling, somehow fills up and becomes the thing. Definitely with BMT [Barely Methodical Troupe] there was so much of that. I was just like ‘we are not finished, this really isn’t finished…but we’ve got to put this thing on stage’. So there’s a lot of that. That felt like it was kind of straight out of the process and onto the stage.

Can you tell us a bit about your experience of working with circus? Your journey and learning. What was your first experience?

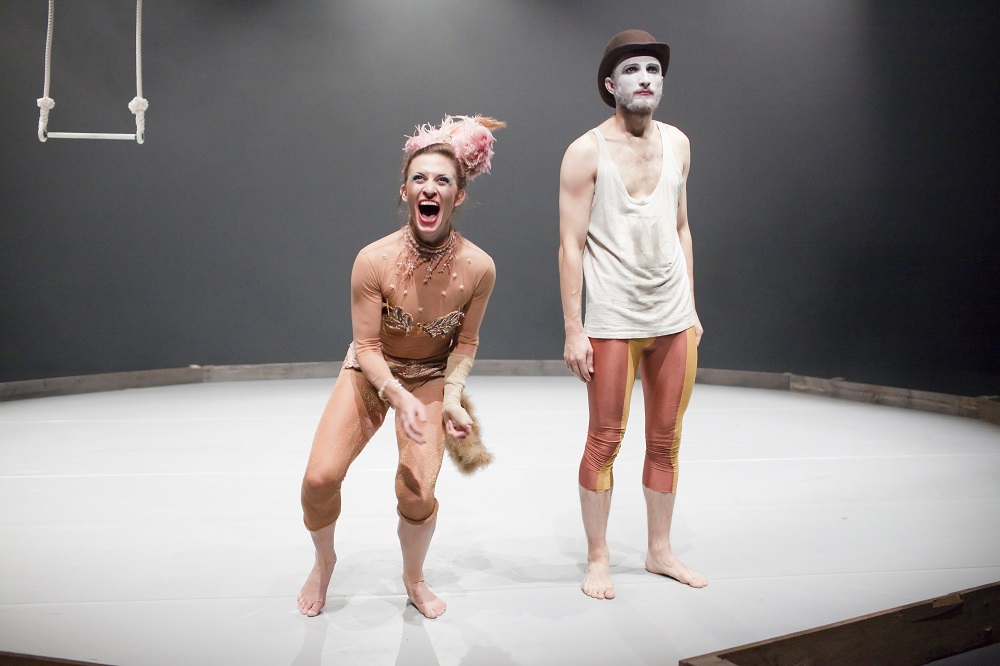

It Needs Horses is the piece that kind of began all of these circus conversations for me. I had watched some circus and I’d seen things like Archaos and stuff like that with juggling chainsaws. It Needs Horses began with this weird idea of it being a competition and a zoo, where you are watching human animals do weird stuff. For this, circus felt more relevant than contemporary dance, where we are often pretending that the audience isn’t there. Circus has a very direct interaction with the audience and something which is explicitly entertaining or is very kind of upfront about the idea of trying to be entertaining, and being entertaining for money. I think the trapeze arrived quite early on and then we just kept putting Chris and Anna in the space with it. There was endless amounts of improvisation, and they came up with lots of crazy stuff. Neither of them had any kind of circus skills and we just kept replaying that moment of the drum roll and the lights going on and… ‘What are you going to do?’

Working with BMT the process wasn’t ideal, because my desire to direct and noodle around, was pulling against their desire to practice and perfect routines and tricks. They are really happy to be making things harder and trying things again and again. That was time-consuming, but I could see it was also kind of essential to the type of show they wanted to make. They want to put stuff in that needs practice, those kinds of tricks that pull you into the reality of the situation, of these people here, doing something incredibly dangerous… But meanwhile, any sense of character kind of flies out the window. And I couldn’t quite find my way into that. Because I want to recognise what that trick does, but I also want to work out how an hour-long theatrical experience, that wants to take a narrative journey, can hold those things within it. They feel irreconcilable in a way. I’m sure they are not always, or maybe they are, but there’s a kind of tension that you can set up between those things, which means that they’re interesting rather than just kind of compromised. Nikki and JD was different because there were two of them and there was more time. The movement into the circus language felt a bit more fluid somehow, and also the subject matter and what they were doing felt more connected at times.

I think that relationship with virtuosity is really interesting. It took me until Paradise Lost to go – ‘‘You know what, I don’t actually need to dance. If I can just say this thing, I don’t need to dance’. Because what is dance doing in this when it doesn’t match the concept? I guess with ballet it’s often the same. You have things like the Nutcracker where there are such flimsy excuses for narrative holding together a series of virtuosic acts. It’s like a cabaret. I guess circus is the same. You spend all this time doing this thing, it would be so weird to do a show and not do the thing that you’re really good at. I found that with BMT particularly, it was like their justification for being on stage was their thing. So between walking on stage and starting to do their thing, there is a gap and in that gap some performers are a bit lost. They’re like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing on stage. I don’t know if I’m allowed to be on the stage until I start doing my thing’. I love those moments because they’re so awkward and then suddenly the performer begins their act and they’re full of skill and confidence… and then when they finish, they’re a bit lost again. Dance has the same problem. We do not spend enough time looking at the idea of being on stage and what performing is, so we want to find ways for people to just be invisible until they’re doing their pirouettes, and to vanish once they’ve finished pirouetting – hence the endless running on and off stage that we see in dance. We’re not very comfortable with that ‘nothing’ space. But we should be, because it’s so fascinating to see people on stage with nothing to do. It looks like a mistake, or a failure. I love failure and they [BMT] weren’t that into failure. I loved the lack of skill and they had a lot of skill. I felt my pull towards failure a lot and I felt like some parts of Kin were kind of imitating the idea of failure, where people were pretending to fail rather than really failing. I guess the idea of virtuosity is always about showing things that I can do that you can’t, and there’s something in there which is challenging but people love going to see people do crazy shit. The question is how long for, I suppose, like, for how long is that interesting? It was such an interesting process and still remains fascinating. I think because of the failure.

Outside of theatre & performance, what influences the work that you make?

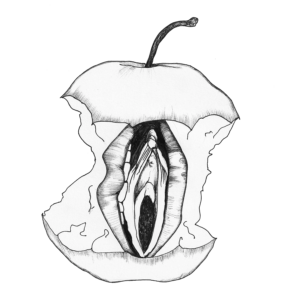

I’d say literature is probably the main one for me. Recently I have been taking other people’s stories as a starting point: a book, or a play, or a story that I have a relationship with. Then the thing that I’m interested in is often kind of pulling apart or looking inside those things, or it’s a slight rewriting of something well known. I also feel influenced by writers like Kurt Vonnegut who managed to write about serious stuff with a kind of humour and a lightness that I love.

(Laura): That makes me think of this scene in Paradise Lost, when you are making the world as God and then your kids are interrupting you. For me that’s a really enjoyable sort of punctuation.

That was a kind of trying to be honest about the process. An idea that somehow finds its way onto the stage. I’m trying to think if I’ve stolen that from someone?… Stand up comedy by Stuart Lee is something else I have spent hours watching. He’s constantly deconstructing what he’s doing as he’s doing it. There’s something in that which I love because it does the opposite of what lots of theatre does, where it’s like, okay, let’s just pretend that we’re in Russia, at the turn of the century, and let’s just ignore the fact that we’re in a theatre. I love the things that acknowledge that we’re all sitting here, which is what circus does by its very nature – let’s acknowledge that we’re pretending to do this stuff. Storytelling as well. Storytelling allows that slippage between the two worlds.

Can you tell us about someone who has been influential in your journey as an artist?

It’s two people I would cite specifically because they mark really important moments. One was a guy called Patrick Wood, who taught me ballet at Lewisham college. I was 25 and for some reason decided that I wanted to be a contemporary dancer and knew nothing about it. Lewisham College did this amazing foundation course, and I got in – I think they were perhaps short of men particularly that year. Patrick taught ballet, which I’ve always struggled with and had a complicated relationship with, but he took me seriously and I am always grateful for that. I was so inflexible. I was so uncoordinated. Just everything about it was wrong. But he took me seriously and he treated me as an artist and I absolutely loved that. He treated everyone like an artist. He had a big influence on me. Lots of teachers at The Place also had an influence on me, particularly Rick Nodine who taught improvisation. I was thinking of leaving because I felt that there was too much technique and I spent my time thinking ‘I don’t get it. It’s too hard. What’s the point?’. There wasn’t enough connection to being on stage and I felt like I was just in a studio, practising for some mythical future event. Rick’s classes were about improvisation and so it was a different kind of technique. He made me see very clearly this connection between performance and improvisation. That kind of cracked something open for me, which meant that the improvisation became part of my process, part of my practice, and it made me feel like I could see the link between physical practice and being on stage.