How would you characterise the work you produce and are interested in developing?

I’m not really a proper producer as I haven’t served my time at the coalface of line producing. I’m much less qualified and rigorous, so I hesitate to hold myself up against people who really know how to put a show into Edinburgh, for example. But what I am good at, is making connections between artists and the rest of the world. So I tend to work with people in the background, scaffolding interactions and helping artists to think about their work from new perspectives.

Stagecraft, theatricality and realisation are very important to me. I like work that doesn’t rely on clever words for people to understand it, and I find it very difficult to read scripts and feel anything, so I tend to work with stuff that materialises in front of you, rather than being laid down on a piece of paper.

Also, I realised more recently, I’m interested in work where the audience has a physical response. So it either makes them cry, or laugh, or it makes them do this thing that you get a lot in circus of [gasping/jumping!]. The reason why I love the work that Ben [Duke, Lost Dog Dance] makes is that you laugh and cry at the same time and you’re like, ‘How am I doing this?!’

One of the biggest things that I am missing about my work is sharing something wonderful with an audience. It’s like a drug, even if you’re not on stage because you go – ‘I worked on that, I made that happen and now you [the audience] are coming out of that show in tears, or saying, that’s the most wonderful thing I’ve ever seen’. And I haven’t had a fix for four months and it’s really, really beginning to show.

Tell us a bit about your journey with circus. Where did it start?

My first job was as a fundraiser at the Young Vic. I joined about two years after David Lan had become artistic director and we were still in the old building, which was a kind of bunker, and my desk was a piece of kitchen surface attached to a wall underneath a window. An Icelandic artist called Gisli Örn Gardarsson had made a circus show of Romeo and Juliet in an Icelandic translation and had written a letter to all the directors of the major producing theatres in England as far as I could tell. Nobody had responded except David Lan, who went out to see the show and met Gisli – who is a tall, charismatic, good looking, energetic, slightly bonkers guy. Gisli took him out riding through the steps of Iceland and to the geysers, and he fell in love with the whole thing.

So sure enough, six months later, this bunch of brilliant Icelanders turned up and premiered their circus version of Romeo and Juliet at the Young Vic [Vesturport 2003]. It was performed in traverse with a runway that went directly across the stage and it had the most beautiful finale… Romeo descends a rope into the Crypt, does all the shenanigans with Juliet and then commits suicide by climbing up the rope and doing something that I’d never seen done before, but now obviously I’ve seen done a million times, which is that he throws himself backwards, outward until he is hanging upside down by his ankles… and the whole audience did that thing of [gasping]… and then sequentially four men on silks, who had been surrounding him like statues, dropped until the show finishes with four dead men hanging upside down on these white silks and Romeo and Juliet having committed suicide in the middle. It was the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen and it spoke to me in all sorts of ways that I never expected. I’d always known that text-based theatre wasn’t really getting to me, but that really confirmed it.

And so a job came up at Circus Space [now the National Centre for Circus Arts], as the head of fundraising and I applied and got it, and over time I kind of wangled my way into more producing stuff so that by the end I had invented this job called Director of Circus Development. Effectively my responsibility was to help artists graduating with the degree and more widely young circus artists, to make the transition from students to the profession. I spent six years in that role having a completely lovely time.

Tell us a bit more about supporting circus artists at The National Centre for Circus Arts and your aspirations there

I think circus is wonderful but what I like about it is that there are still enormous questions – I’m very interested and driven in finding how you can ally really high-quality circus skill, with the depth of meaning and understanding you find in other performance work. Because somehow that doesn’t always deliver. One of my aims in mentoring students at the National Centre was to get them to think about what they wanted to say, rather than just finding clever ways of twisting their tricks so that they had meaning. However, it’s a challenge for them. Firstly, because they’re 19 – and potentially they’ve been in back to back gym classes since they were nine – so often they don’t yet know what they want to say, and secondly they’re having to try to find out what they want to say at the same time as exhausting themselves learning these new skills. So whilst I’m interested in pushing creative innovation, I really didn’t want to make them feel that there was some kind of standardised form of success, and at their graduation I’d say to them, ‘you’ve gained this amazing toolbox of skills, now work out what you want to do with them’… And some would set to work on an ACE application and some would go and join a company and some would go straight into a great Christmas contract. And that diversity and range of opportunity is great and I loved supporting them with all of it.

How do your personal politics influence the work that you do?

I’m not a natural activist. I enjoy political work, and I admire the people who are prepared to engage in it, but I’m not drawn to work on it myself. I am a white, heterosexual, privately educated woman. I’m a walking bundle of privilege and I’m not sure anyone needs my views taking up space. I am liberal to the core of everything I believe and feel, but I’m aware that when I witness injustice, which of course is very relevant at the moment, I tend to hide behind my liberalism. I don’t feel able to take a strong position, because I feel that everybody has a right to do and be the thing they are. So I draw heavily on the political biases of the people that I work with. My reasons for working, with Extraordinary Bodies, for example, are not political, but I fully engage and embrace the political stance that Clare and Jamie and the team there take, because I agree strongly with it.

Can you tell us about an experience of seeing a show that really stands out in your memory?

Notes from the Field, which is an Anna Deavere Smith show that was at LIFT Festival a couple of years ago [2018]. It’s an exploration of the number of young black people that are imprisoned in America and how that comes about. The show was unbelievably powerful and the things that she was saying were like – ‘Holy shit can that really be true!’ – But the central thing I remember is her physicality and stagecraft. She did this thing where she switched from being this slouchy teenager to a kind of hellfire and brimstone preacher at a lecturn, just by taking a hoodie off. Just in that moment. It was better than anything I’ve ever seen. By the end of the show, she had the whole audience in tears and on its feet singing Amazing Grace. I was just like, ‘Holy crap, how did she do that?!’ It was amazing.

Can you tell us about a producing journey that has really stuck with you?

About 10 years ago, my husband was doing an MA in historic building conservation and he took me to a place called Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park in London. It’s in Mile End, right out in what used to be the fringes of London but now is actually the middle. The park is a derelict Victorian cemetery, the last person to be buried there was in the ‘50s and it’s now a wildlife conservation area. It’s one of those really spooky places, covered in ivy with trees growing through the middle of graves. You step off the Mile End Road, which is roaring with traffic and you walk into this other world of snaggle-tooth, higgledy-piggledy tombstones and complete silence. And for some reason I thought – ‘God wouldn’t it be amazing to do a circus show here’.

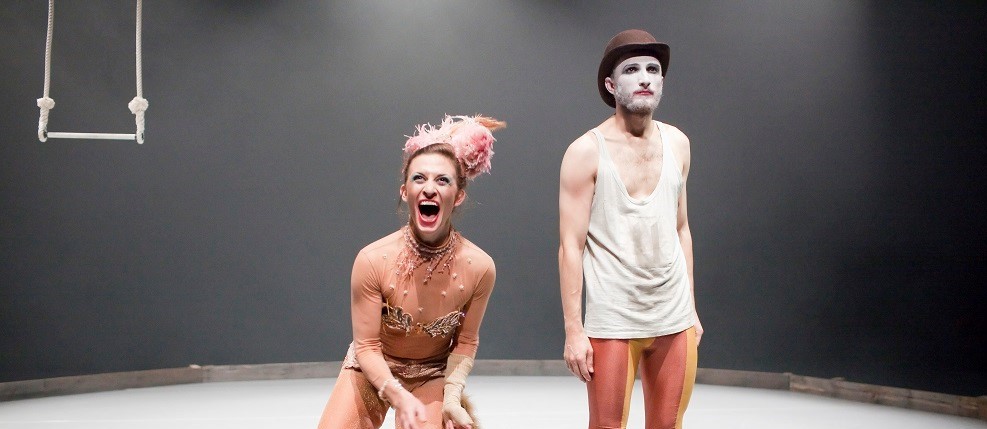

Three and a half years later. I’m sat next to Mark Ball, who at that time was the artistic director of LIFT, at an industry lunch. Mark doesn’t say very much and I talk a lot when I’m nervous, so I talked at him for about 20 minutes and told him about the cemetery… he just kind of nodded and I’m like – ‘Gosh, I’m being so boring’ – so I shut up and turned to the other side. And then about two months after that, I got an email from him saying, ‘Can we talk about cemeteries?’… And about two years and two children after that, LIFT came on board with Circa, Spitalfields Music and the National Centre and we created a show called Depart in Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park. It was directed by Yaron Lifschitz from Circa and featured 12 Circa artists, 16 National Centre students and 12 students from Central School of Ballet, plus an amazing community choir from East London. The audience walked through the cemetery at dusk and encountered these beautiful moments, with an original soundtrack by Lapalux. The whole thing was completely amazing.

The following year we toured the show to Hull, Blackpool and Brighton. I went to see the Brighton show in Woodvale Cemetery, which has got a modern bit which is still in use and then a whole bit off to the side on a hill, which nobody ever goes to. So the journey through the show was up this hill towards a finale that took place on a stage, overlooking Brighton, with the sea and, that night, a massive electric thunderstorm in the distance. At the end of show, the whole audience of 400 people had to walk back down the hill together – and it was the greatest pleasure I have ever had in anything, walking amongst those people, who had come to see something when they didn’t really know what to expect, in a place that is dedicated to solemnity, and who had had that gripping, visceral response that you get from circus. It was one of those amazing moments. Partly because that producing journey had been so epic, and had started with me visiting that cemetery and talking too much to Mark, and ended with a thunderstorm on a hill in Brighton.

What are your current aspirations in your work?

One of the things that drive me at the moment is that I’m really interested in work that can make the hearts of huge audiences beat stronger. I remember seeing James Thierrée do a one-man show in the Barbican Theatre [Raoul 2009]. He made up for the one-man-ness by having this enormous set that like, flew, did wild stuff. But the thing that I remember most about that show was something that he did with his fingers. He came to the front of the stage, he told a story with his hands. And behind him was this huge set, with like sails and loads of stuff, but all I remember was this thing he did, just here.

So I really enjoy the kind of craziness of scale, and I am curious to see how the power of a story or performance, can touch people in a 2,500 seater theatre, in the same way as it would a rural touring audience of 50 people. There’s this sense that in order to fill that size of theatre, you have to have so much stuff and I’m interested in how stagecraft can allow you to have the same effect with much less.