Can you give us an insight into your curating or devising practice? That could be making your own work, or work you direct, or both?

My work is very personally driven, so it often starts around identity politics or something from within me. I did a piece called Jewess Tattooess because I’m from a traditional Jewish family and I chose to get loads of tattoos and, you know, be a bit of a wild card. And I wanted to kind of explore that. It was such a rich vein of imagery and cultural ideas. The Ghost Train [Carnesky’s Ghost Train] kind of came out of my solo work Jewess Tattooess, ‘cos it was all about old and new, traditional and non-traditional, and woman and her body as a site of memories or pain or conflict, and also as a sexually expressive thing.

I also have a few dominant themes that I’m always playing with, kind of cultural obsessions. British seaside culture, Fairground variety and entertainment traditions, female entertainers, anthropology, migrant identity, sexual representation and ritual in performance. I love fairytales and symbolism, and for that reason, I really like the horror genre, the surrealism and the exploring of the unconscious within that. And then on top of that, I am coming from a place of exploring cultural identity, and from a Jewish background looking at immigration, and then also looking at current feminist issues that affect me. So, I just, I like a lot of things, and maybe that makes the work complex. I think for me it’s like a jigsaw puzzle. You’ve got lots of things that you’re interested in and you’re trying to put it into one show, into one clear idea. How do you do that? How do you combine these interests?

Dr Carnesky’s Incredible Bleeding Woman came from an image from a horror movie from the early 80s, where a woman is miscarrying, her dress is bleeding and bleeding, it’s kind of an arty strange film called Possession. And I was like – ‘I want a bleeding dress. I want a kind of a high collar bleeding dress and I just want to bleed and bleed and bleed’. And it was from that image that the whole PhD and the whole show came. It started with an image. Working on that show, it was quite new to my practice to explore things around menstruation. I wasn’t even looking at women’s health, particularly. I was more looking at what I’m interested in, which is the symbolism there. I brought in performance artists Florence Peake and Kira O’Reilly at different stages, to work with me and the collaborating cast, as dramaturgs. In the show, we were exploring the idea of reinventing cultural rituals of menstruation… We had hair hanging with Fancy Chance, and we were doing sawing [a person] in half with blood, and I was talking about how menstruation and magic were connected, and then Florence asked ‘but what’s the show really about?’. I had been playing with this idea of touching on my experiences of miscarriage, but I was experimenting with how to frame it, I was thinking ‘….my work is coded… it’s symbolic… for me, the sawing in half piece is about miscarriage but I don’t want to stand there and say it’, and she said ‘just try it, because you’ve not put your story in’. I then found a way that I felt comfortable voicing my experience without feeling overexposed or too far away from my practice. Gradually we started to articulate it more and create a dialogue with the artists in the show to really address their stories in the work. Kira really understands aesthetics and helped me finally refine all the research and emotion into the performances and get them the way I wanted. ‘So Rhyannon, you know you’re a trans woman, you don’t have a womb, you don’t menstruate, you can’t have children. Let’s say it’. And then, that work actually became the heart of the show – and then I’m like, ‘how do we do this in a way that’s still theatrical and fabulous and show women and blood and colour and horror movies and anthropology and menstruation?!’

Can you tell us a bit about your experience working with circus?

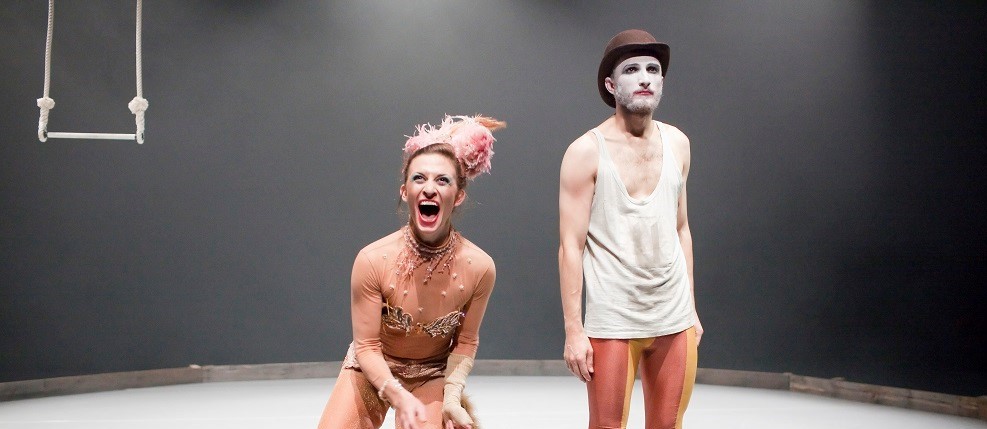

I love the aesthetics of old British circus. Like, really in your local park, spit and sawdust, working-class circus, which obviously is quite different to French circus. I also just love things that fly. I am obsessed with it. When I was a little girl, in every show I would imagine I would be flying in this show at some point, or somebody would be flying. So it was always something I wanted, circus, and I wanted to work with illusion as well. These were two big areas for me.

One of the reasons I like working with circus artists is because they are really used to being collective and there is a lot less ego flying around the room. I don’t know if I am a circus outsider or an insider? I have always had a strange relationship with it in that way. I play around with magic illusions, but I haven’t been a tumbler, you know. The nearest thing I could say is that I am a bit of a clown, but I never went to Gaullier and trained, I just kind of figured it out for myself.

What else influences the work that you do or the work that you make?

Well I love cinema and I am a big film buff and I love surrealist cinema and I love music and I used to go to lots of gigs and live in squats and that sort of thing. [Laura: Favourite bands?] I love…I dunno who do I love? I love My Bloody Valentine. I loved them in the ‘90s, kind of like a wall of noise, and my first love was a British woman called Danielle Dax who was kind of psychedelic goth from the ‘80s. I loved her. She never got as famous as she should of. And I love really camp things. I love Lydia Lunch, shes a kind of punky poet, a caustic New Yorker spitting pith at the world. That sort of thing. All quite punky, underground. I always remember one of the things I really loved when I was younger was the Lindsey Kemp Company….David Bowie was in the Lindsey Kemp company, Kate Bush did time with them too. They were sexually explicit. They were queer. They were deeply camp. Theatrical. So British in so many ways. I was so enamoured with Rose English who brought a White Stallion on to the stage and did this extraordinary meditation on the showgirl.

How do your personal politics influence the work that you do?

Yeah well very much so. I think I try to be very political with the work in my own way. I am very interested in promoting a kind of left-wing feminist politic at all times, in everything I do, and being very clear about that. I also think the work is political in terms of the choices that I make for the work. I put the Ghost Train on in Blackpool for five years, where there were not so many arthousey shows at the time and employed all local young people. It wasn’t a huge art career move, you know, and I guess I knew it was more of a community project in that sense.

Getting a career off the ground is in the way you manage projects and how you work with people. And how you treat people – the relationships between artists and performers and companies – is at least half of the success of it. If I bring a collective of people together, it’s important to me that they get to have their voices heard, transparency of contracts, the scale of pay – all of that is really crucial because you know, I was a performer, I want to treat people the way that I would want to be treated. And I want to challenge some of the old traditions that might relate to more patriarchal ways of doing things. Sometimes creatively that gets in the way because I want everyone to have a voice and I feel they must be represented in the way they want to be, and that can mean I lose a little bit of control over the aesthetic. It’s a fine balance. If I’m going to use real people, and they’re going to use their real stories, how do I find the line between having a directorial and aesthetic eye over the whole project, and respecting and harnessing that person’s voice? I think negotiating that has been as difficult as getting funding and getting my own ideas.

So can you tell us about the experience of seeing a show that really stands out in your memory? What did it feel like? What was the show company? Can you remember what you were doing or working on at the time?

I saw Flowers by the Lindsay Kemp company, which is based on Jean Genet’s book, and it just blew my mind. There was a kind of otherworldly quality in the use of lighting and strong visual images, really bright. Lindsey Kemp was a mime artist. Queer mime. Mime is so frowned upon but I love it, I love it from the 70s! Proper, old fashioned mime mime – Let’s get mime hip again! …So yeah, I was young, 16, and I just remember the space, the lighting, the smoke and this kind of otherworldly, not woman, not man…just literally slid across the stage. It was magic and it was live and that really moved me.

I also really loved Romeo Castellucci’s Genesi, which was huge Italian visual theatre, like he makes the stage breathe. People were flying in and out and there was this strange museum bit with people with really different bodies in glass cases.

Another show that changed my life was Annie Sprinkle’s Post Porn Modernist in the early 90s. I was obsessed with her: she just blew my mind. And seeing that show blew lots of ideas I had about everything.

Can you tell us about an exchange you had with a member of your audience during or outside of a performance that has stayed with you?

I did Jewess Tattooess at the Acco festival which is in a Palestinian town in Israel. This was a long time ago, 20 years ago? A Hasidic woman came up to me afterwards and she said, ‘I don’t agree that you’ve had all the tattoos but I understand and I feel it so, and I feel like I have tattoos’. So that was interesting that the work spoke to a woman from a completely religious community. There I was, naked, tattooed, cutting a Star of David into myself, and that had resonated with a Hasidic person, who was potentially completely opposed, morally, to the things I was doing. Art can cut across that, you know. I am happy when my work helps make unexpected connections and dialogues between people.