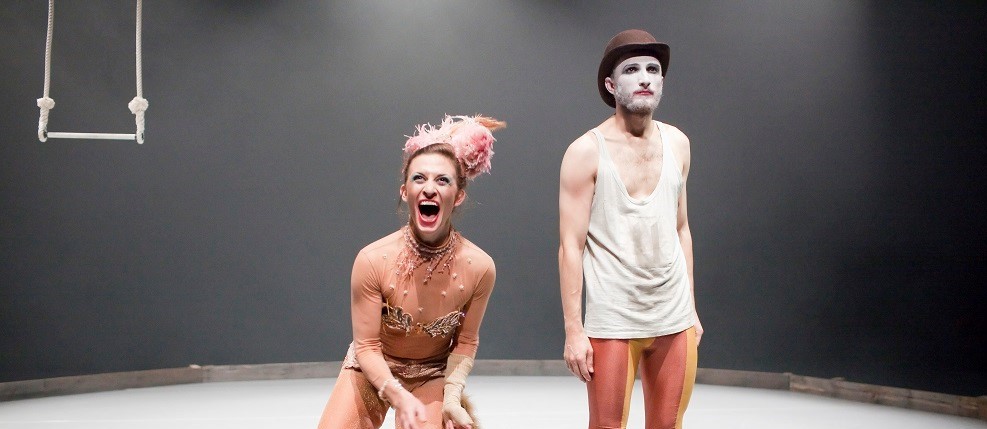

I find it so important that I’ve spent the last 7 years of my performing and academic careers celebrating historic Jewish circus families. We can – and should – appreciate what brought a person to where they are today.

However, as I watched the statue of Edward Colston topple to the ground during the recent Black Lives Matter protests in Bristol, I was made to think about the role that celebrating lineage has had in perpetuating current power structures. I found a recent opinion piece in the Guardian particularly interesting. It drew my attention to the fact that the UK parliament continues to give titles, political power and land to people with “good lineage”, including those whose ancestors made their money through slave trading and colonial practices. Whilst Colston’s statue has been removed from Bristol’s aesthetic consciousness, it’s obvious that the invisible statues, the power structures the effigy symbolised, are still standing in many forms. The ‘living statues’ in the House of Lords are a breathing example. If lineage shapes the makeup of those selected for prestigious public positions and the wealth and influence that follows, it means that the ethics and actions of Britain’s colonial past are still being recognised and celebrated. This recognition shapes our present, reinforcing ideas of western and white superiority and holding them steadfast into the future.

An interaction online recently reminded me that the custom of inherited wealth and respect, of “good” lineage, which commits us to repeating historical power structures, is also something we reinforce in the way we treat each other in circus. I expressed an unpopular opinion in a circus Facebook group and the first attempt to discredit me was the microaggression “What circuses have you toured with?” – They were checking my lineage. Because lineage in circus is not only biological, it’s also professional. It’s the people and institutions you descended from, who shaped you and made you who you are, who taught you what you know and whose legacy you carry on. Some of the first questions we ask a new circus friend is where they trained and where they worked, and we construct a vague pre-assumption of their artistry based on their answer. This fishing for credentials has the potential to credit or discredit, to link a person to what already has status and power, or to demonstrate the lack of that link. In contemporary circus there is an emphasis on high-level physical skills and athleticism, education at prestigious schools with cutting edge techniques, performing with successful established companies and the physical presentation that those schools and companies expect and sustain. Measuring people against these qualities perpetuates a value system that impacts on the circus industry, in terms of access, participation and aesthetics. Only a select few people can fit that mould, and there are numerous factors that can affect one’s suitability including race, sexuality and economic status.

In her recent article Running Away to Join the Circus and Finding Out It’s Racist Noeli Acobi discusses an exchange with a casting director who told her “you don’t have the right look” and questioned why her thighs were so large. Acobi goes on to explain that the standard of ‘the right look’ is often used as a reason for not casting non-white artists. She proposes a call to action from circus companies to consider the power that they hold and asks casting directors to think about their ‘unconscious bias in the hiring process’. When the circus industry places such a strong emphasis on certain qualities, it stifles diversity and creative development. What important artistry do we miss out on as a result of this particular set of standards and requirements? The aesthetics and standards set by the circus industry shape the image of role models and peers – if you don’t see someone like you involved you get the idea you shouldn’t be there. In order to create an environment that welcomes any and all individuals, regardless of any lineage credentials (family, school or company) they may or may not have, we have to question our social behaviours. Changing the value of the circus is a slow process, but we as artists and members of the community need to stop reinforcing and checking people against the values that have been set. Lineage checking is one of many ingrained behaviours that perpetuate old and problematic value systems. We need to own up to the not-so-inclusive lenses we apply in our spaces and communities, and actively work to change our viewpoints – as individuals, as an industry and everything in between. Appreciating one’s origins is a blessed thing – just as long as lineage doesn’t shape the mould in which we cast the future.