Tell us a bit about your work and your practice, what are you currently focussed on?

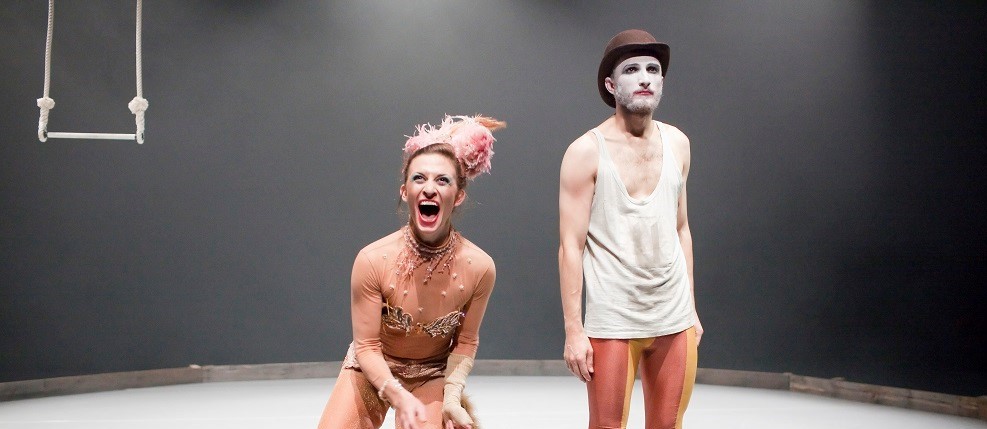

For the last ten years, I’ve been developing my show Elephant. It’s a multidisciplinary work with theatre, live music, circus, audio description and sign language. I first wrote it as a monologue, at about the same time as I started training circus. Elephant is about how you do or don’t fit in when you are disabled and unsure of your racial identity. All the performers are deaf and/or disabled and we use access in a creative way. The most important thing about the show is its potential to inspire other people who are disabled and to show able-bodied audiences the unlimited creativity of disabled performers and disabled artists. There might be a kid who is D/deaf or disabled, who experiences the work and says ‘I want to do that’ and knows through seeing us that it’s possible.

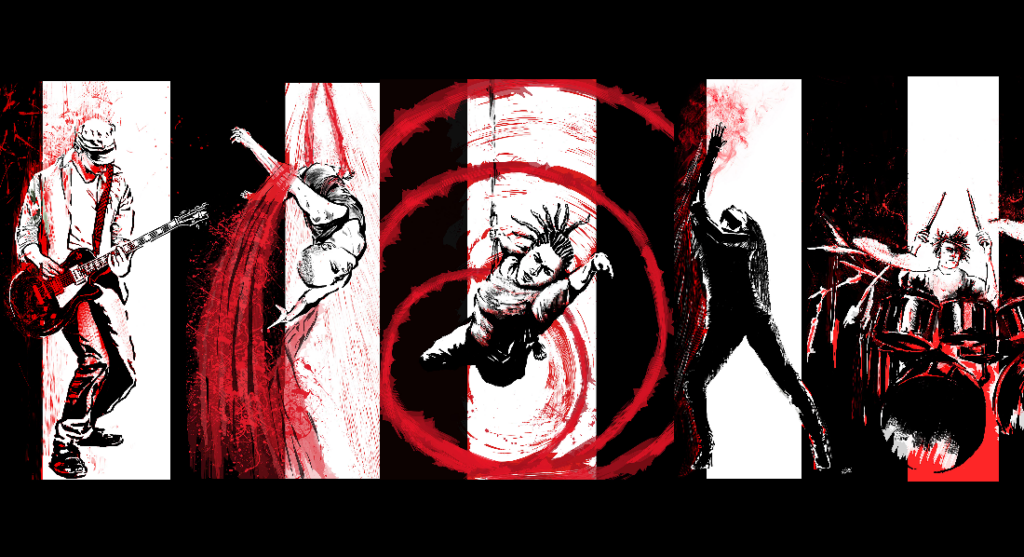

That said, I really don’t like the way that, in general, people see disabled performers as inspirational or “brave”, regardless of what we do on stage. For me, it’s important that we push ourselves to do something that we haven’t done or seen before, and just work out the things we need to learn to make that happen. Every member of the Elephant cast always pushes themselves to learn and do more. When I spoke to Chris Campion, the visually impaired musician who is composing the music and said ‘I really want you to audio describe the show’, he said, ‘Yes, let’s do it’. Or when I spoke to Natasha Raffi Julien, a Deaf dancer and asked her if she wanted to challenge herself to learn Chinese pole in two weeks, she said, ‘yeah, I’ve never done a show like that’. In rehearsals she just kept going and going, even though it was really painful, until she nailed her choreography. Or Jonathan Leitch who is an aerialist and a drummer in Elephant and who is a wheelchair user. At one point when he is doing hoop he asks me if there is a way to put his wheelchair up in the air and use it as an aerial apparatus. It is really exciting to see. When thinking about how can I challenge myself, I decided that I’m going to write the show, I’m going to learn to do Chinese pole, aerial hoop and play the guitar. Because that takes me out of my comfort zone, and there is nothing more exhilarating than achieving something that you, or others, doubted you could.

What performance communities do you work with or feel part of and why?

Elephant is about that. Resisting categorisation. Trying to fit in the way that you are and at the same time understanding that you will never fit in. Being mixed race and trying to fit in with my white friends, but I’m not that white. Trying to fit in with my black friends when I’m not that black. Or being disabled and having people ask me, am I actually that disabled?

I describe myself as a multidisciplinary performer or artist. Some people would describe me as an aerialist who’s now doing acting, even though I have trained and performed as an actor throughout my life. Others see me as an actor who ‘does aerial’. When I say that I am a musician as well, and I write plays, that’s when I feel people stop trying to confine me to one label. Sometimes you try to pigeonhole people, or try to put people in places and say ‘I get you’, but you don’t look at that person properly. If you look at Amelia [Cavallo, Elephant cast member and co-director of Quiplash], walking down the street with a cane, you’re like, ‘Okay, there’s a blind person’, and right there and then you decide that she’s not able to do a whole lot of things. But then you see her work. She does silks and Chinese pole. She plays the bass. She plays the keyboards. She sings whilst doing silks. How do you define someone like Amelia?

Can you give us an insight into your curating and devising process?

We have two visually impaired persons, a wheelchair user, a deaf performer and me, all on stage together. So the rehearsals have to be extremely well organised. And then as well, you have to consider the theatre, circus and music elements. Onstage, we need to give musical cues or visual cues to each other, which have to match the needs of each individual. For example, in a particular moment, Jonny’s drums are a cue for Amelia, who is visually impaired, to know when to come down from the silks and for Chris, who is also visually impaired, to know when to finish or start a guitar solo. There are a lot of layers to the work, including audio description for the Chinese pole act and the BSL script, which at times playfully interrupts and contradicts the spoken script on stage. When you see the whole thing together you see this immense, cool, cohesive thing, cos we have spent so much time with each other and learned to play music with each other. We are all in awe of each other and I envy them all: Johnny, the way that he plays the drums; Amelia, the way that she does everything; Chris, his music; and Rafi, who dances while signing and signs whilst up the Chinese pole.

Making Elephant has provided opportunities for us all to learn different aerial disciplines. There aren’t a lot of opportunities for disabled people to learn and to become experts in Circus. We know that there’s not a lot of circus companies who are willing to employ disabled performers and that becomes an obstacle for us to progress. There aren’t schools willing to teach us. There are plans for courses and training opportunities to happen, but nothing has happened yet. Everybody seems not to have the availability or the will to teach disabled people how to be circus and aerial performers. So we have to create those opportunities ourselves.

Outside of theatre and performance what influences you in the work that you do?

I’m a Nichiren Buddhist, and when you practice Buddhism you take responsibility for your issues. You become a Bodhisattva Of The Earth – a being who is responsible for spreading the Buddha’s teachings, (which say everybody can overcome their problems and be happy). They do that by overcoming a Karma they have chosen in a remote past and in doing that inspire others to overcome their problems, whether they are Buddhists or not. I believe that I chose to be disabled and mixed race way back before I can remember. That helps me to not be constantly angry with the world. I have to remember that I chose this life. This way of thinking made me understand that you can create your own life and do your own thing. So instead of being angry with the performing arts world because it’s not very accessible to disabled people, I’m like ‘Let’s create our own opportunities! Let’s do it and let’s find the people to do it with!’

What’s next for you?

I’m working on Elephant and I’m writing a play at the Soho Theatre as part of the Writers Lab.

The play I am writing with Soho Theatre is about hate crime, towards disabled people and about violent, physical oppression. The main character is a black disabled teenager. There aren’t a lot of stories about being black and disabled and I think that the next step for disability arts will be to bring our narratives to the mainstream world. I’ve also just been granted a micro award from Unlimited to research and develop a new piece of writing which explores how people behave in the workspace during lockdown and the impact of social distancing on relationships.

Can you tell us about someone who’s been really influential in your journey as an artist?

I have inspirational moments that I tap into when I feel down and there’s always this moment that I go to when I was eight or nine. In Portugal, in year six everybody has to play the recorder. So I go home and say, ‘Mom, I need a recorder, everybody’s got to learn’ and my mom said ‘are you sure you are going to be able to play the recorder? You don’t have fingers. Why don’t you talk to your teacher?’. When the day came and everybody had brought their recorders, the teacher played a note and everybody would tweet the note and then she would say ‘and now Milton’. This carried on and on and on until I had to use all my fingers and eventually my teacher said ‘I’m sorry Milton, but you cannot play the recorder’. That silence, so many kids looking at me. When I arrived home later crying my mom said, ‘what is it?’ and I said ‘I can’t play the recorder, the teacher said I couldn’t play the recorder’. My mom had seen this coming and she said ‘there’s some stuff you’re not going to be able to do in your life and recorder is one of the things. But there is going to be loads of stuff that you are going to be able to do. The important thing is for you to do stuff that you like. Some stuff that you like, you’re not going to be good at. I really like singing but I’m not a singer. But I fell in love with teaching and that’s what I do now. So you’re going to find in your life one or two things that you’re going to really fall in love with and you’re going to be able to do that, really, really well. So forget about this recorder thing, just go to the class and don’t worry about it’.